Top 10 Employment Law Developments of 2018: #8 – Equal Pay Redefined

TOP 10 DEVELOPMENTS OF 2018 IN EMPLOYMENT AND HIGHER EDUCATION LAW:

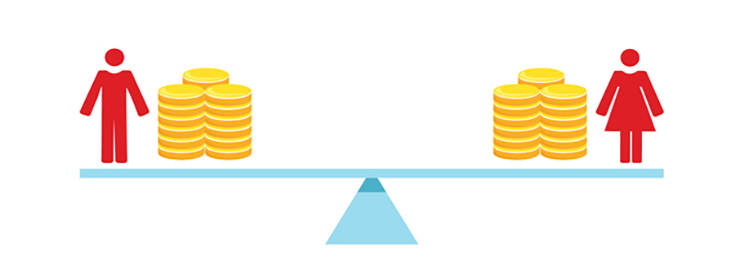

NUMBER 8 – EQUAL PAY REDEFINED

Pay Me What You Owe Me: Aileen Rizo Redefines the Equal Pay Act

I imagine that Rihanna and Aileen Rizo are kindred spirits. Rihanna topped the charts with a song demanding to “pay me what you owe me” and is herself a phenomenal businesswoman and advocate for women; Aileen Rizo is a groundbreaking woman who shone a light (you might say she shines “bright like a diamond”) on the struggles that women face in seeking equal pay for comparable work. This past year, Aileen Rizo’s quest for equal pay for comparable work led the Ninth Circuit to take what is the strongest stance on equal pay in the United States in Rizo v. Yovino.

Background

Aileen Rizo, a math teacher with two master’s degrees and years of experience teaching, took a job as a math consultant with the Fresno County Office of Education in 2009. The County utilized a standardized salary schedule and placed new employees on the scale by taking their previous salary and adding 5 percent — that prior salary was the only criteria for determining an employee’s rate of pay.

Rizo was placed on Step 1 of the schedule, but after three years, she learned that a male colleague with the same title, with less experience and education, was hired at Step 9, earning $17,000 more than her. Her complaint to the County fell on deaf ears, as did her lawsuit at the trial court and before a panel of three judges of the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals. But that was not the end. The Ninth Circuit agreed to hear the case en banc and it reversed the three-judge panel, in an opinion issued on April 9, 2018.

Equal Pay Act

The Equal Pay Act (EPA) was signed into law by President John F. Kennedy fifty-five years ago. As the Ninth Circuit states in Rizo, “[t]he Equal Pay Act stands for a principal as simple as it is just: men and women should receive equal pay for equal work regardless of sex.”

Under the EPA, a plaintiff is only required to show that her employer pays male and female employees differently for substantially equal work, which the Ninth Circuit characterized as “a type of strict liability,” since intent is irrelevant; however, even after a plaintiff makes this showing, employers may justify disparate pay based on an exception encompassed within the statute. Many lower courts have interpreted these exceptions broadly to permit almost any justification as long as it is related to a business purpose. The Ninth Circuit disagreed, requiring that the County articulate a job-related factor to justify a pay difference, and absent such evidence, the pay discrepancy is unlawful under the EPA.

The Ninth Circuit found that consideration of previous salary alone is not a job-related factor, an easy decision in its view since the U.S. Supreme Court has rejected what it viewed as a related justification, the so-called “market forces theory.” That long-rejected theory was that it was not unlawful to pay women less than men, because systematic pay discrimination has historically driven women’s compensation lower and has led women to accept lower salaries because they cannot find higher salaries elsewhere. The Ninth Circuit found that when setting compensation, consideration of only an employee’s prior salary history was merely an extension of the “market forces theory” and thus rejected it.

In Rizo v. Yovino, however, the Ninth Circuit took another unprecedented step, holding that any consideration of previous salary at all was impermissible under the EPA when determining compensation, finding that prior salary “is not job related and it perpetuates the very gender-based assumptions about the value of work that the Equal Pay Act was designed to end. This is true whether prior salary is the sole factor or one of several factors considered in establishing employees’ wages.”

It bears noting that the County has petitioned for review by the U.S. Supreme Court, but unless the Court agrees to hear that case, the Rizo opinion remains the law in the Ninth Circuit.

California Equal Pay Act

In the last legislative session, California also attempted to address equal pay on the state level. The bill (AB 2282) amends the California Equal Pay Act effective January 1, 2019, to allow employers to make compensation decisions about employees, including current employees, based upon the employee’s current salary, as long as the employer can also point to another justification that is not sex-based. Thus, unlike under the EPA, under the California Equal Pay Act, employers may consider previous salary in conjunction with other permissible factors (such as the employee’s experience, training, level of production, or seniority). The California Equal Pay Act, which is structured similarly to the federal EPA, is broader than the EPA in that it applies not just to sex-based discrimination in pay, but also race-based discrimination in pay; thus, employers must consciously review their compensation practices as they compare for all employees, not just male and female employees.

In addition to allowing employers to consider current salary in conjunction with other permissible factors, AB 2282 clarifies expectations and requirements for providing salary scales and requesting salary information from a job applicant. It clarifies that employers are only required to provide salary scales to applicants for employment (not current employees), upon request, and only after applicants have completed an initial interview. AB 2282 also authorizes employers to ask employees to ask applicants their “salary expectations” for a desired position.

A note of caution, however, as some municipalities, such as San Francisco, prohibit employers from asking an employee about their salary history, and, as seen in the Rizo case, such information cannot be taken into consideration when setting a new employee’s salary under the federal EPA.

What to Do in 2019

Employers should take this time to review their salary practices before the new year and consider a pay equity audit. Equal pay claims are poised to increase in frequency in coming years and employers would be well-served to have investigated their practices and salary differentials.

Employers also need to ensure that HR professionals know that in California, they cannot inquire into past salary history, though there is nothing preventing employees from choosing to share that information voluntarily.

Kaitlyn Schwendeman is an associate in Hirschfeld Kraemer LLP’s San Francisco office. She can be reached at (415) 835-9002, or kschwendeman@hkemploymentlaw.com.